“Every message, whether editorial or advertising, has to be sold by immediately revealing its importance to the reader.”

Having been raised in the environment of serious editorial design (my father is Jan V. White, a noted magazine designer and author of 25 books on the subject who was called by Communication Arts magazine “America’s design philosopher”), I initially fell a little far from the editorial tree and, though I spent my summers through college working in the art department at Architectural Record magazine at McGraw-Hill, I was attracted to advertising design. I practiced it in New York City at BBDO (in the ultra-sexy all-tv “Pepsi Group” under the leadership of Phil Dusenberry, who eventually rose to Chairman of BBDO and was inducted into the American Advertising Hall of Fame) and then at a much smaller outfit, Homer&Durham. But, despite enjoying a pretty promising career arc, I couldn’t see myself selling sugar water and New Zealand lamb and cruise ship rides for the rest of my creative life, so I went to grad school.

At the time there was a huge split between editorial design and advertising design. The two disciplines were seen as quite different and were taught that way. My background already was equally balanced between the two areas, and this perceived difference was confusing to others. I wrote my second book, Type in Use (the 2nd Ed’s fourth printing was in 2003), which is a guide to understanding a publication’s essential typographic elements. A few more years went by and I wrote my fifth book, Advertising Design and Typography (in its third printing), and the circle was complete. Having spent thousands of hours thinking and writing about typography and editorial and advertising design over nine books, I could legitimately state that, from the reader’s perspective, there is no difference between editorial and advertising design. Readers respond to – or fail to respond to – all visual messages just about the same: if they perceive value to themselves, they stop. This is true for online messages, too.

In brief: Every message, whether editorial or advertising, has to be sold by immediately revealing its importance to the reader. And that is exactly what I help my editorial or advertising clients achieve.

Please note that my approach to design is collaborative with my clients. The first and most important step I undertake is a diagnosis of the problem. We should be spending a goodly portion of our time diagnosing or defining the real problem. When we finally get to a full and correct diagnosis, the design solution should reveal itself. In other words, a thorough diagnosis produces its own naturally-suggesting design solution. The diagnosis is codified in a bulleted job brief that describes the project’s requirements and defines the design purpose. It is a clear statement of what the problems are that are to be solved in the design development stage. A well-written job brief ensures my clients get back a design they think represents their organization’s mis en scéne rather than something that I alone “like.” This is the most efficient and satisfying process for all of us.

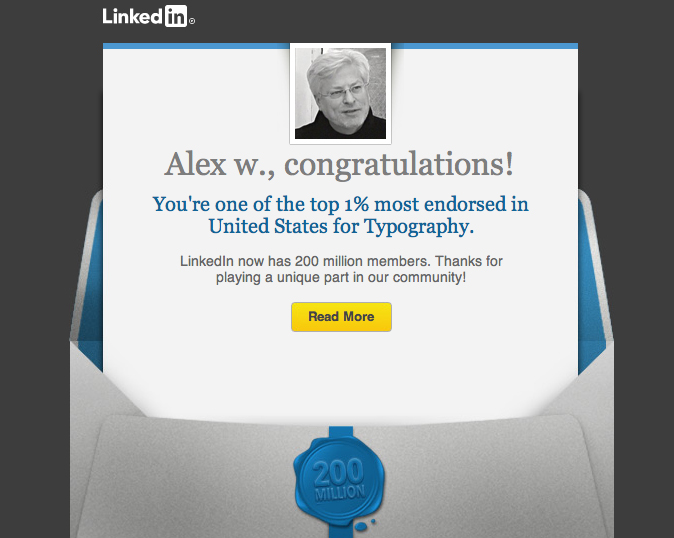

Top 1%. Top 1%? Top 1%!

A completely organic surprise. What a lovely thing to be told. Thank you to everyone who endorsed me.